Intimacy and dignity with the doctor. About communication like from a movie and patient rights

Published April 19, 2023 09:00

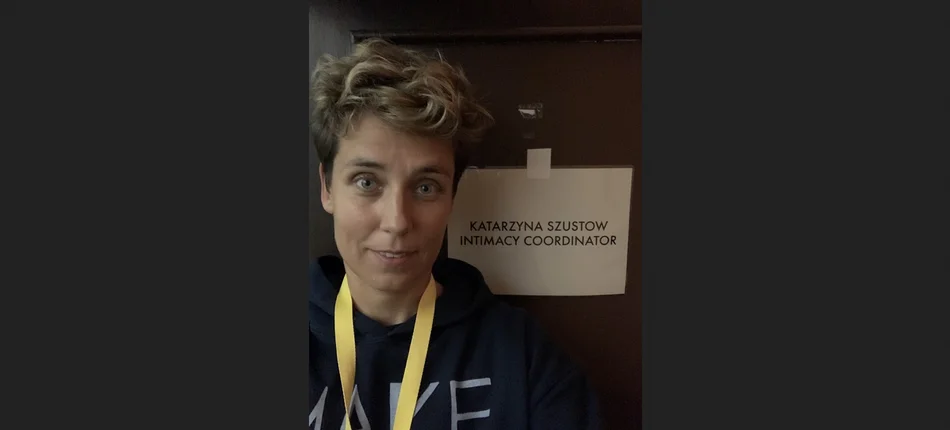

Medexpress: Working as an intimacy coordinator in the film and theater industry is a whole new profession-a sign of changing times and of recognizing the importance of consciously built relationships between people. And intimacy, you say, is for you a combination of security and trust. Tell us what your work consists of.

Katherine Szustow: The trust between actors that you see in a scene is already the end result. It's that icing on the cake that has to be built together beforehand. The first stage of work begins with reading the script. Everyone needs to understand what world we are entering and what we are going to tell the story about. The second stage is to confer with the director, the filmmaker and understand their vision, so that we know what kind of passion, intimacy (or lack thereof) is to appear in the film and what we want to tell the audience with it. The next point of work is to talk to the actors and very often there is a theme of boundaries and assertiveness, that "no" is a full sentence. We talk to them about what is the role of coordinators of intimate scenes on the set, what we help them with and what can be expected of them, and what not necessarily. Intimate scene coordination consists of the principles of the five C's, and I also add a sixth.

Medexpress: What's underneath them?

Catherine Szustow: It's: consent, which means "informed consent" or "acquiescence." It's important for actors to know that no one will manipulate them, they'll get full information about what we're doing and why we're doing it, how we're building the character, and that they always have the right to withdraw, even at the last moment when everything is worked out. I have had this situation twice. It's usually related to their personal experience, and you have to be aware that working with actors who have experienced previous traumas looks different, among other things because the body's memory is non-rational. Another "C" is context, or "context" the actor knows why and why he has to undress in a scene, why he has to perform such and not other things on his own body. We talk about the character, the scene - not about their personal lives, unless they are talking about their experiences, which were difficult for them and can influence our work. The next "C" is communication. Communication should be transparent, based on non-violent agreement. There is also a "C" like choreography, meaning each scene has its movement and gesture directed. And closure means closing the character, closing the creative process. The coordinators suggest exercises to help you get out of the role - for me this is important so that the actors are not left alone with the "grieving process" after the film is finished. And to these principles I add another "C", which is community because I believe that working on a film or a play in the theater is teamwork. That's one part, the other is working on the script, practicing with the actors, for example when we work on body sense. You can tell the actors to trust each other, but that won't work, it takes work. Then we go onto the set, and that's where you need to coordinate arrangements from all verticals.

Medexpress: That last "C," that is, character closure-how is your work in this aspect?

Katherine Szustow: Closing a character is a very intimate moment for an actor. I give them exercises to do on their own at home. But some actors have their own techniques. In addition, after about two weeks I send them the so-called "feedback form", in which they share their thoughts, comments from working on set with me. Feedback in creative processes is a novelty. Until recently, no one had the right to evaluate anyone. I think this "test" of my competence, as well as a test for the whole production, is incredibly developing. Actors have the opportunity to share their thoughts on the whole process. We have insight into whether a production has met safety level standards, but we can also grow by creating a better work culture, as well as honing the craft of this youngest of filmmaking professions.

Medexpress: What exactly is it for you to work with actors from the perspective of an intimate scene coordinator?

Katherine Szustow: Working with actors is working with their boundaries, but also with the shame that everyone has in them, and this is worth emphasizing: an actor also feels shame, even though he is expected, by virtue of his profession, to forget it. This is actually a work with how we were raised and shaped by family and society. Our cultural attitude to the body, for example, is heavily influenced by the hegemony of the Polish Catholic Church. After recognizing the boundaries and needs of the actors, we work with the director's vision, and this is the most fascinating thing about this work - how to convey the directors' imagination through the choreography of touch.

Medexpress: As you talk about the six "C" principles, I think about how much of this area is transferable to building a doctor-patient relationship. Some of these "C's" would come in handy as rules to streamline a patient's visit to a specialist's office. Not to mention that the patient is also expected to hide his or her embarrassment during the examination. What do you think doctors and patients lack in their relationship, which after all requires trust and a sense of security?

Katherine Szustow: It's difficult for me to give an opinion on this subject, because it's not my industry. I'm a fairly healthy person, with health care fortunately I have little contact. I suspect that it is similar in this area as in others. We are seeing a gigantic generational change and at the same time a generational conflict. There are more and more young patients who are familiar with tools such as nonviolent agreements, paying attention not only to "what" we communicate, but also "how." This is due to growing up in a different geo-political reality. I grew up in parallel with the capitalist system, which infused us with the shock doctrine, only now do I see how much economic, symbolic or even physical violence we experienced as teenagers. Often the doctors who treat us started their careers while they were still in the old system, where violence was top-down institutionalized. Whoever was harsher, more vulgar, was somebody. The question now is how to work with this rift? How to build communication between young patients and, for example, older doctors? How to use an assertive attitude at the same time without risking being overlooked by the doctor on whom our lives depend? I myself am shocked at how my 11-year-old son often argues his "no" sometimes. I know it's not just my work at home, but also the school, the one in which he grows up in the education system (formerly Swiss, now German), which teaches him to give answers in a polite but assertive manner, without the traits of violence. But what is interesting is the style of communication in dentists. Every time I am given information about what will happen during the procedure, and the doctor is polite and aware of the touch. Is this related to the fact that you have to pay for dental care in Poland in most cases? Is it a matter of the fact that a visit to the dentist is one of the more intimate, delicate situations due to working with patients' faces? An open mouth and immobilization is an extremely unpleasant situation that can trigger anxiety or panic attacks in some. Maybe dentists have developed a better way of communicating with their patients, because unpredictable patient reactions make their work difficult?

Medexpress: Good question. The Patient Ombudsman 's website describes one case of violation of a patient's right to intimacy. The information provided there reads: "A 17-year-old female patient reported to a gynecology clinic with her father for a cytological examination. The midwife performing the test stated that the patient's father must be present at the examination. The patient twice, clearly articulated her objection to the presence of her father in the office, however, the midwife firmly stated that the patient's father was to be present at the examination. As the patient's father indicated, the midwife performing the examination informed him that due to the nature of the examination, his presence in the office was essential." What do you think happened here?

Catherine Szustow: This is an example of extremely violent behavior, which shows, on the one hand, the cruel character of the midwife, but also the lack of proper procedures - a person working with nudity, according to me, must have basic competence in interpersonal communication with patients, and must know the legal regulations. It's important to look at procedures - I believe there is power in them and they can change the reality of the relationship as well. The patient, who is probably at the beginning of her sexual journey came to the doctor with her parent, apparently she needed it. However, the very presence of her father in the office was already clearly opposed, she had the right to do so. In Poland, it is enough for 16-18 year olds to present their guardian's and their own consent for examination or treatment. The midwife broke the law by requiring the presence of a parent at the examination. Violence happened here on many levels: a young woman was treated cruelly by a woman older than herself (where is the female solidarity?), her bodily boundaries were violated in the presence of a man who is related to her, her opinion/request was ignored (trust in the health service will take a long time to rebuild), the autonomy of a person who will be of age in a few months was violated. But the father, who was honored in this situation because he did not know how to behave, was also harmed. He reacted only later and filed a lawsuit (which probably required a lot of courage, as well as sleepless nights). I think this kind of situation is the ubiquitous Polish penchant for violence - for me it is a deep echo of years of unhealed traumas, starting with uprisings and wars, lack of respect for procedures, rules, and low soft skills of Polish "specialists." I once heard strong words from my father that I was the first generation of "non-murderers." It is worth looking at what we got from our parents and what we pass on to those around us.

Medexpress: When you say that there is strength in procedures, I understand that in them we can find a sense of security, that they do not strip us of our emotions and are not "inhumane" at all.

Katherine Szustow: Security is built on procedures - you know what to expect. There is no sense of safety without clear rules. In the case of the teenage patient's story, the midwife who broke consciously (or not) established procedures failed. Ignorance does not explain the harm done.

Medexpress: There are still, unfortunately, many examples of violations of patients' right to respect the right to intimacy and dignity. A classic one is a round at a hospital, when a doctor discusses a patient's case with students, without asking if they mind telling about the patient's health situation so that everyone next to them can hear and see.

Catherine Szustow: Learning from practice is part of doctors' work. It is a good idea to ask permission from the sick person. The way the question is posed and the reason or context is important. The doctor should introduce himself, say, for example, that he is accompanied by 20 male and female students who are learning knee surgery, and this lady's knee is a phenomenal case (a sense of humor tames difficult situations). And ask: What do you think about this topic, so that we can talk about your case? A closed question ("Can we...?") that can only be answered with "yes" or "no" presses us up against the wall. Especially when those 20 students are waiting for an answer. Few will then say "No, I don't wish to."

Medexpress: As patients, we buy into a certain belief and expectation system. I'm at the doctor's office then I have to undress for the examination, forget instant shame, etc. We automatically push aside our boundaries. What lies beneath such a scheme, what is the problem?

Katarzyna Szustow: This is a question about Poles' trust in the health care system and doctors. The Ipsos 2022 Global Trust Monitor shows that this trust is at 39 percent. Here you have to go back to history. Polish capitalism is a young system. The level of poverty in which we grew up was downright shocking. Thinking about trust, security in that former system, or communication was an abstraction. We are now in a period of great social change. Young people, who now drive the elderly crazy with their empathy and emotionality, calling some violent situations, are giving us training in respecting each other. This is shock therapy, given how we have been talking to each other recently, at least in offices. There is a mega change for the better. In trust, it is certainly helpful to always name one's own barriers, i.e. when going to the doctor, we have the right to expect the doctor to tell us how the examination will look like before he conducts it. On the other hand, you also have to think about his situation, the fact that he sees 30 to 50 patients in a day and has only a few minutes for each one, and may also be overtired and struggling with other problems outside the office.

Medexpress: Recently I was in the hospital for a few hours as a patient. I encountered many people, nurses, registrars, doctors. No one looked me in the eye.

Katarzyna Szustow: Looking into each other's eyes in Poland is an interesting thing. Poles and Polish women are not culturally taught to look each other in the eye. It was a forbidden gesture for hundreds of years, which is influenced by Polish history - on the one hand, peasants as enslaved people who were forbidden to look into the eyes of their masters, on the other hand, more than 100 years of partitions, wars as well as years of communism with its obsession to control female and male citizens by militia and other services. Although Poles are more willing to peep at people thinking that others don't see them surreptitiously looking. The Swiss in such situations lower their gaze. This always makes me laugh. The first thing I noticed after moving to Switzerland is that many people on the street look into each other's eyes and greet each other with a smile. Artificial or not, indifferent. This was completely new to me: a smile for a child and his or her parent, a glimpse into the eyes. So I would not expect in Poland to look into each other's eyes. Moreover, the gaze communicates different things - especially when we are naked. People are afraid of sight because it connects us. Not everyone is ready for intimacy. There are times when someone doesn't look in the eyes because he is nervous. Isn't it better to offer such a person a conversation while walking? We don't look into each other's eyes while walking side by side, but it's easier to talk.

Medexpress: It's hard to take a walkout with a doctor.

Katherine Szustow: But you can properly arrange two chairs in his office one in front, the other sideways, next to the desk. I have seen such a solution in Poland. This shows that the doctor is aware of how emotions work in his office. Other things in the office are, for example, a curtain behind which we undress at the gynecologist's, or even better, a separate room closed with a door. There are many solutions that can be implemented in a doctor's office space that will make communication easier.

Medexpress: Susan Sontag said of the disease that it is our "more burdensome citizenship." When a patient enters a doctor's office with this burdensome citizenship, it , I guess, is stressed, like an actor before playing a difficult scene. What could we use, what communication techniques, to manage our stress about our bodies and illness?

Katherine Szustow: I would start with the assumption that doctors should not be expected to empathize. A doctor doesn't have time to empathize with his patient. That's not what he's there for. He's there to understand what's going on with the patient and issue a correct diagnosis quickly, which is problematic in this timeframe (8-16 minutes). And here I come back to the rules about interpersonal communication: a doctor can use them if the situation requires it, if he sees a patient coming to him who is shaking with nerves, for example, a woman who is before a gynecological examination. The doctor, in order to calm her down, can say that he notices her emotions so that she doesn't feel invisible in the office. This will help the patient feel better. Telling the patient what is going to happen step by step and why specific tests are done is probably an extra 90 seconds. It builds trust. I suspect that patients who trust doctors get better faster, but this is pure hypothesis. For patients who are afraid of examinations and visits to the doctor, it would be good for them to work with their emotions, e.g., punching their fears - what exactly they are afraid of: cold instruments, white coat, awkward atmosphere in the office, diagnosis, etc. Putting emotions only in your head is a bit like functioning in a mess after a party. Working with a pen and paper opens up other areas of the brain. It's easier to rationalize what we're experiencing. In addition, writing a note for yourself "When I start to get nervous, then..." where you name your reactions (e.g. faster breathing, wet hands, accelerated heart rate, etc.) helps you understand your automatisms. It's worth finding your regulating exercises - there are a ton of them on the Internet.

Medexpress: You say not to expect empathy from doctors. Meanwhile, the topic of empathy and the lack of it on the part of doctors comes up in virtually every workshop on doctor-patient communication. Its necessity in the relationship with the patient is even talked about by lecturers at medical universities. What should we actually understand by the term "empathy"?

Catherine Szustow: Most of us intuitively understand this category as empathizing with another person. Empathy consists of four competencies: the ability to accept another person's perspective (accepting that everyone has their own truth), getting rid of judging the other person (giving up advice, suggesting solutions), recognizing the other person's emotions (being able to notice and name them), and being able to empathize with the other person (this is difficult when we don't understand our own emotions). From a doctor we expect good advice, but also an assessment of risky behavior, accurate diagnosis and clear guidelines. Empathy is therefore difficult in the doctor-patient relationship. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to see the patient as more than just an illness and use techniques to facilitate communication.