Take a deep breath and the vaccine

Published July 19, 2022 13:37

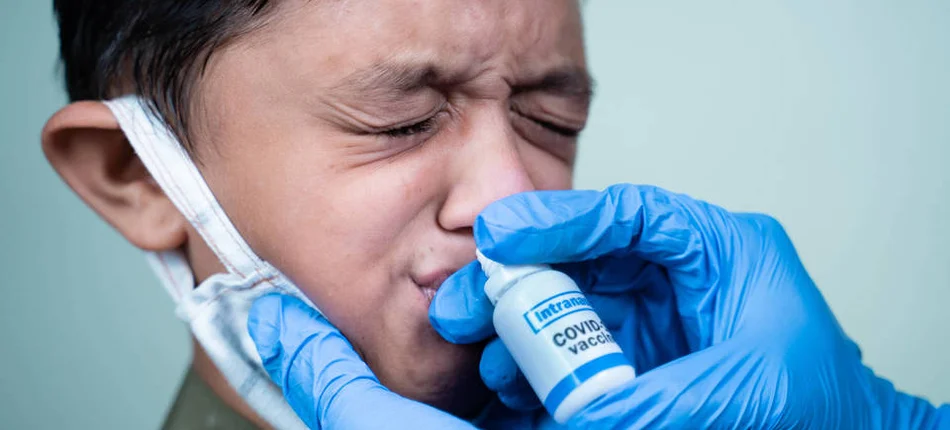

While drug makers are outdoing each other in updating first-generation vaccines for the next fall pandemic wave, other scientists are working on developing a vaccine that is delivered either by nasal spray or oral tablets. And while this is not a new idea, Dr. Ellen Foxman, an immunobiologist at Yale School of Medicine, expressed her hope that this form of the vaccine would help strengthen defenses already in the nasal cavity, the first part of the airway, so that the virus cannot replicate there. "That would be the holy grail," said Foxman, who works for the International Congress of Mucosal Immunology in Seattle. If this works, the hope is that mucosal immunity could slow the development of new coronavirus variants and ultimately contain the pandemic.

Before that, however, there is a long way to go. Many scientists say this approach requires massive funding. Ed Lavelle, an immunologist at Trinity College Dublin, says what didn't really happen with mucosal vaccines is the enormous technological advancement that has been made with injectable vaccines, and that is funding clinical trials.

Could Nasal Spray Vaccines Suppress New Coronavirus Variants? More than a dozen nasal spray vaccines against COVID-19 are tested around the world. Many of them use new types of technology, incl. proven mRNA. In animal tests, intranasally or orally vaccinated hamsters were less likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2 infection to uninfected animals that were housed in separate cages.

In turn, one of the companies is conducting advanced research on the vaccine in the form of tablets. The Vaxart tablet, which is the size and shape of an aspirin, uses adenovirus - the same system used in Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines. In an early trial of 35 participants, 46 percent had an increase in nasal antibodies after taking the vaccine tablets. Those who did appeared to create a broad spectrum of resistance to many types of virus variants, and maintained that protection for about a year. Next summer, Phase 2 of the study is to be completed, involving almost 900 people.

Most of the nasal vaccines under development will be intended for use as booster doses in people who have received the core COVID-19 vaccine series. "The new generation of vaccination will build on the immunity that was produced by previous injections," said Jennifer Gommerman, an immunologist at the University of Toronto who specializes in tissue immunity.

One attempt to test such a variant of the vaccine was made by Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at Yale University. The research team vaccinated the mice with a low dose of Pfizer's Comirnaty mRNA vaccine and two weeks later administered a dose of mRNA vaccine in the form of a nasal spray. The low dose of the injected vaccine was supposed to simulate declining immunity. Other groups of mice received only an injection or only a dose of intranasal vaccine. Only the group given the injection followed by the nasal spray vaccine developed strong immunity to the COVID-19 virus.

The researchers explain that mucosal vaccines target a slightly different part of the immune system than those given by injection. The injection causes the body to produce antibodies against the virus that causes COVID-19. Most of them are Y-shaped proteins called IgG antibodies that are programmed to recognize and block specific parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus along its spines, parts that attach to and infect our cells. A much smaller proportion of them are IgA antibodies, which look like two Ys linked together, resembling a dog's bone. IgA antibodies are the main guardian of the immune molecules in the mucosa. These molecules are more potent than IgG antibodies. They have four arms instead of two and are less "picky" about what they grab compared to IgG antibodies. Traditional vaccines increase the IgA antibodies in the nasal cavity for a short time, but the hope is that mucosal vaccines will really increase the population of these guards and help them stay active for longer.

Iwasaki wants to move to human clinical trials as soon as possible. Will it succeed? It depends on the money.

Source: CNN