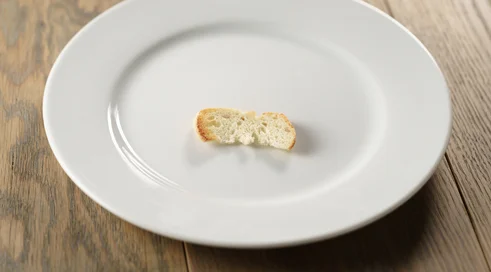

A good meal in the hospital. Is it even possible?

Published Sept. 22, 2023 08:11

Debates about hospital nutrition standards have been going on in various public health bodies for years. They gain prominence in successive election campaigns, but so far this has not led to changes for the better. Proper hospital nutrition still leaves much to be desired even though it was established long ago that diet is an integral part of the treatment and recovery process, reduces the risk of postoperative and other complications. As a result, it helps shorten a patient's stay in the hospital. It would seem that the problem of hospital diet is niche, because it concerns those who are currently being treated in inpatient facilities. However, it stirs up public emotions, as anyone can one day fall ill and require hospitalization.

A report by the Supreme Chamber of Control five years ago showed that there are many irregularities in nutrition in Polish hospitals. It enumerated, first of all, inadequate balancing of menus inadequate to the health of patients, too small a share of products that are a source of wholesome animal protein, too many products with low nutritional value and high fat content, underestimation of the energy value of food, improper distribution of energy between meals, and overestimation of salt content. It has also been noted that meals are prepared from low-quality products. Tests of samples of hospital meals, conducted at the request of the Supreme Audit Office (NIK) by the authorities of the State Sanitary Inspectorate and Commercial Inspection, in turn showed nutrient deficiencies that could cause harm to patients' health. The list of irregularities is much longer, and it also includes issues of the sanitary safety of the food served and the cleanliness of the premises where it is prepared or sorted for distribution. Aesthetics are not even worth mentioning.

According to the program, the nutrition rate per "person-day" will be increased by PLN 25. This will make a big difference, but it will not be enough to bring about changes. This is because the organization of patient nutrition is a very complicated mechanism and depends on many factors. First of all, there is no separate fund for nutrition. The costs of nutrition are covered by hospital treatment contracts with the National Health Service, which include medical and accompanying services. It is on the latter, on which what a patient has on his or her plate depends, that hospitals often try to save money, if only because the cost of the treatment itself is often higher than the value of the NHF contract. Currently, the feeding rate in a large hospital in the capital is about 33 zloty plus vat. In smaller towns it's 16 zlotys and less. Inflation affects what can be offered to the patient for this money. There are also no mechanisms to support hospital nutrition, which is not a therapeutic activity under the law. Another factor affecting the standard of hospital diet is the size and location of the facility (large city, medium city, small town) and the question of whether it has its own kitchen or uses catering. Many hospitals have had to abandon this type of activity due to regulations on running kitchens in medical facilities. This has been forced by equipment regulations and the associated costs, but also by the difficulty of obtaining staff. Switching to catering services means mandatory participation in tenders and selection of the financially most advantageous, i.e. cheapest offer. Tender prices are shaped locally. Their level depends on the region in which the hospital operates, its size and the distance from the hospital of the service company. In large cities, the market is firmly divided between several catering companies - tycoons who can afford to bid at low prices. For hospitals and their financial capabilities, of course, this is a relative concept. The tender is won by those entrepreneurs who operate on a macro scale, fulfill orders in the thousands, and are profitable to supply hospitals at a competitive price. However, mass production of healthy food is demanding in terms of the products used. So the circle closes, as it is difficult to combine high quality products with an ultimately low price for the finished dish. It should also be said that meals prepared at a distance from the hospital lose quality and taste during transportation.

The so-called "input to the boiler" is not the final cost of feeding patients. The hospital incurs other related expenses. Intra-hospital food distribution should be included in the "person-day". This is carried out by specially trained and employed people for this purpose. In large hospitals, this is at least a dozen to several dozen employees. Washing and cleaning of dishes and waste is also a cost. The hospital must also provide supplemental dietary ingredients such as nutridrinks and electrolytes. On top of this, there are mandatory dietary reserves for patients coming to the ward outside meal times or at night. It is customary to have to provide products from which to prepare "emergency meals."

The hospital diet must cover the patients' energy requirements (2300 kcal) and all the nutrients necessary in the process of treatment and convalescence. In the case of people with diet-related diseases, it should be meticulously tailored to the patient's needs in terms of ingredient content, method of preparation, energy value. The hospital must take into account that there are patients with allergies or who require food with special texture. Another group is vegetarians and vegans requiring a separate diet. It is right, therefore, that the draft regulation provides for the employment of at least a part-time dietitian who will control all this substantively. Meanwhile, dietitians in hospitals are rare. The first reason - hospitals save money on these positions, the second - is the relatively low salaries, which are not competitive with the private sector. A hospital dietitian has such an immensity of responsibilities that it is impossible to imagine that he or she can cope with them on a half-time basis. These include. planning, supervising and implementing group and individual nutrition for all groups of patients of different ages, keeping records of patients' nutritional status and nutrition, developing diets, supervising the preparation of meal distribution, supervising the catering company, planning menus for at least 7 days ahead, taking into account the type of meal and composition of products, energy value (caloric content) and nutritional value (the amount of protein, carbohydrates, including sugars, fat, saturated fatty acids, salt per 100 g and portion of the meal), the method of processing and the presence of allergens. In theory, there is also cooperation with the doctor when it comes to special needs patients, such as those who are malnourished or struggling with obesity and other diet-related diseases, as well as education of patients being discharged home. In addition to this, the dietitian's duties also include checking cleanliness and billing the catering company. So it's easy to guess that even in the smallest hospital, a dietitian will have a bang for the buck, and faced with an excess of responsibilities, he or she will quickly start looking for a new job.

In the context of low dietary rates, staff shortages, requirements for clinical dietitians, and the need to save money on everything, it is hardly surprising that a model patient's plate is rare in Polish hospitals and patients satisfied with hospital food are in the vast minority. The ministry's draft proposes changes to diets at every level. However, it distinguishes between mass nutrition and nutritional treatment. The draft considers only the former, i.e., standard meals served to patients as a necessary component of hospitalization-an accompanying benefit within the meaning of the Law on Publicly Funded Health Care. So one can be happy about the proposed higher rate, but in essence, in the context of the complicated procedure of hospital nutrition, there is little chance of change. This "throw in the kitty" will not meet all needs. Money is needed for dietary staff and hospital food distribution personnel. What's more, training for doctors who do not have adequate knowledge of diets is proving necessary, as well as changes in regulations governing nutrition and the employment of those dealing with this part of hospital reality.